While Appalachia Counts Its Dead: Predatory Pharma's Growing Profits in a Yearslong Epidemic

How pharmaceutical corporations exploited Appalachia's vulnerabilities as an extraction zone for profit, mirroring patterns of predatory capitalism seen in the Global South.

In Sullivan County, Tennessee, Alice McCaffrey has witnessed the quiet devastation. As director of the Sullivan County Anti-Drug Coalition, she watches as overdose deaths climb year after year, even as they fall elsewhere. "Fentanyl was still the primary driver of Sullivan's overdose deaths in 2023," McCaffrey explains. "Stronger counterfeit pills and illicit drugs were available, putting people who didn't realize what they were taking at risk.”

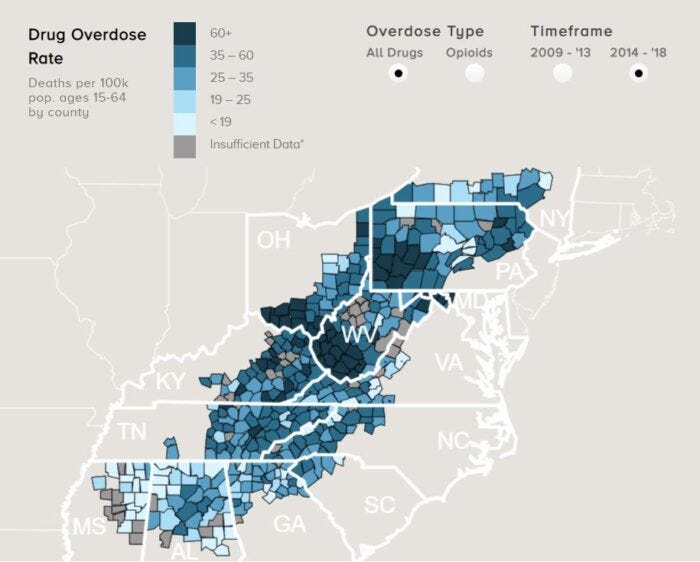

In 2023, while Tennessee celebrated its first year-over-year drop in overdose deaths since 2013, Northeast Tennessee saw an increase. The 270 lives lost represented a 2.3% rise from the previous year. Sullivan County alone saw 93 overdose deaths, up from 77 in 2022.

What's happening in Appalachia represents a form of what anthropologist Philippe Bourgois calls "predatory accumulation"—a process by which capital extracts wealth not through productive enterprise but by exploiting vulnerability, connecting this region's experience directly to patterns of exploitation seen in the Global South. As pharmaceutical corporations targeted Appalachia as an extraction zone, they generated immense profits while communities bore the costs of addiction and death—a pattern that mirrors how multinational corporations operate in vulnerable regions worldwide.

Appalachia as Predatory Capitalism's Profitable Extraction Zone

Appalachia has long been familiar with extraction. Coal companies removed wealth from beneath the mountains while leaving behind polluted streams and broken bodies. The timber industry stripped ancient forests. Now pharmaceutical corporations have extracted profit from Appalachian pain through opioids, treating the region like an internal resource colony—similar to how the Global South has been treated by multinational corporations.

The region's vulnerability was engineered through generations of what economic geographers call "uneven development." As coal jobs disappeared and alternatives failed to materialize, economic depression brought physical pain from dangerous remaining jobs and psychological distress from uncertain futures. Into this environment, pharmaceutical companies introduced a new solution: pain management through opioids.

The roll-out of OxyContin in 1996 by Purdue Pharma targeted regions with high rates of workplace injuries and disability. Sales representatives flooded doctors' offices with promotional materials claiming that opioid addiction was exceedingly rare, occurring in less than 1% of patients—a claim later revealed to be fabricated .

"The pharmaceutical industry is one of the largest and most powerful lobbying groups in the United States," notes Paulo Pereira, who has studied the expansion of opioid use across the Americas. This influence, coupled with what Bourgois identifies as the "revolving door" between government regulatory agencies and the private sector, created the regulatory capture necessary for predatory accumulation to flourish.

By 2012, there were enough opioid prescriptions in the United States to supply every adult with their own bottle of pills, with the highest concentrations in Appalachia (CDC, 2020a). In Washington County, Virginia, where I grew up, enough opioid pills were circulating to provide each resident 72.2 pills per year between 2006 and 2019. Nearby Wise County had 116.6 pills per person. This was not coincidental but strategic—a deliberate flooding of vulnerable markets with a product engineered for dependence.

The Mechanics of Predatory Accumulation: From Pills to Heroin to Fentanyl

What makes opioid capitalism "predatory" rather than merely exploitative is its pattern of profit-taking without sustainable value creation. As Bourgois notes, predatory accumulation "is not capable of reproducing itself through licit productive processes of stable, exploitative surplus-labour extraction through legal mechanisms." Instead, it produces profits by destroying its own customer base (Bourgois, 2018: 390).

In Greene County, Tennessee—which reported the highest overdose rate in the region at 67 deaths per 100,000 residents—this predation unfolded through multiple stages. First came prescription opioids, marketed as safe and non-addictive. When regulations tightened around 2010, many users transitioned to heroin, which was cheaper and more available. Then came fentanyl, an even more potent synthetic opioid, often mixed into counterfeit pills or heroin without users' knowledge.

“Over the past 10 years, the drug landscape in the United States has shifted, with the opioid threat (controlled prescription drugs, synthetic opioids, and heroin) reaching epidemic levels, impacting significant portions of the United States,” according to the 2017 DEA National Drug Threat Assessment.

Each stage generated profit while increasing harm. Pharmaceutical companies made billions on prescription opioids. When restrictions came, organized crime networks stepped in to meet the demand that had been cultivated. The markets shifted, but the predation continued.

This pattern mirrors what researcher Sasha Breger Bush describes as "ecological Taylorism"—the industrial process of breaking down nature into ever more specialized and profitable components. Just as the poppy plant was reduced to its most potent compounds, Appalachian communities were reduced to their commercial potential as sites of consumption.

The Machinery of Predatory Capitalism: Regulatory Capture and Medical Complicity

The genius of predatory accumulation in the pharmaceutical sector lies in its ability to mobilize legitimate institutions to serve market expansion. While street dealers faced decades in prison for selling small amounts of illicit drugs, pharmaceutical executives devised marketing strategies that would lead to hundreds of thousands of addictions and deaths.

The medicalization of pain as "the fifth vital sign" in the 1990s—a shift heavily influenced by pharmaceutical industry funding—created the conditions for widespread opioid prescribing. Doctors became unwitting agents in this system of predation, while some became witting accomplices, making massive profits like other participants in this drug network.

"These pharmaceutical conglomerates have enjoyed state support to make their undertakings feasible," notes Pereira, describing similar patterns in Latin America. In Appalachia, this support came through Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements that made opioid prescriptions financially accessible and profitable to prescribe. This revolving flow of money and drugs between corporations and government support located individual addicts in the middle, as the profit-making through-put needed to justify the drug’s existence and as objects to feed the drug.

The FDA's approval of OxyContin in 1996 based on limited evidence of safety illustrates this dynamic. As Bourgois documents, Curtis Wright, the FDA official who oversaw OxyContin's approval, left the agency shortly afterward to work for Purdue Pharma.

The machinery of predatory capitalism involves a revolving door of mutual beneficence between state and market actors.

Externalizing the Costs: How Predatory Capitalism Transforms Deaths into Footnotes

What makes predatory accumulation in the opioid economy insidious is how effectively it transforms human suffering into an externality—a cost borne not by the profit-takers but by communities, families, and public institutions.

In Sullivan County, where overdose rates stand at 59 per 100,000 residents, as Keeling reported, this externalization takes many forms: emergency medical responses, treatment programs, law enforcement, lost productivity, child welfare services, and overwhelmed foster care systems.

Most devastating are the intangible costs that cannot be monetized: grief, trauma, and lost human potential. These burdens fall disproportionately on rural Appalachian communities that were already struggling with economic precarity.

"Barriers to treatment remain too high," McCaffrey notes. "Stigma prevented many from receiving the support they needed to recover" (Keeling, 2025). This stigma itself is part of the predatory system—by individualizing addiction as a moral failing rather than recognizing its structural drivers, it deflects attention from corporate culpability.

From Big Pharma to Foreign Threats: The International Politics of Blame-Shifting

As the crisis grew, blame shifted from pharmaceutical companies to "Chinese producers and Mexican cartels." This redirection of blame obscures the ongoing responsibility of domestic corporate actors who initiated and profited from the crisis.

This international framing mirrors what Pereira describes as a process by which pharmaceutical corporations "export to the 'foreign' the contradictions inherent in the opioid control policy that underlies the capitalist logic of drugs.” The emphasis on foreign threats allows domestic corporations to deflect responsibility while continuing their predatory practices.

Focusing exclusively on these factors misses the structural conditions that made Appalachia particularly vulnerable to predatory accumulation—the economic disinvestment, high rates of workplace injury, inadequate healthcare infrastructure, and the regulatory capture that enabled aggressive marketing of addictive substances.

Global Circuits of Predatory Capitalism: From Appalachia to Latin America

As awareness of the opioid crisis increased and legal consequences began to materialize, pharmaceutical companies adapted by expanding to new markets.

Bourgois documents how pharmaceutical corporations, facing regulation and negative publicity in the United States, have begun targeting new markets in Latin America and Asia (Bourgois, 2018: 394). When prescription opioids became more difficult to obtain in Appalachia, the market shifted to heroin and then to increasingly potent synthetic opioids (Schuchat, Houry, & Guy Jr., 2017).

The logic of predatory accumulation requires continuous expansion to new markets or products as existing ones become saturated or regulated. This pattern mirrors what David Harvey calls the "spatial fix" of capitalism—the need to continuously open new markets to absorb surplus capital and maintain profitability (Harvey, 2004: 64).

Pereira documents how Mundipharma, a network of pharmaceutical companies owned by the same family that owns Purdue Pharma, has been expanding aggressively into Latin America, using the same marketing tactics that fueled the U.S. crisis. This global circuit of predatory capitalism connects Appalachia directly to vulnerable communities across the Global South, creating parallel crises of addiction and exploitation.

Beyond Predatory Capitalism: Reclaiming Appalachia's Future

What would it mean to move beyond this pattern of predation in Appalachia? It would require more than just addressing symptoms through naloxone distribution or treatment programs, though these are essential for saving lives.

It would demand a fundamental reconsideration of how capital relates to communities made vulnerable through historical processes of extraction. The "free market" in pharmaceuticals has been shaped by regulatory capture, information asymmetries, and the exploitation of vulnerabilities.

As Moore and Fraser argue, harm reduction initiatives often "conceptualize drug users as rational and free to make choices, thereby ignoring and failing to remedy the structural issues that may lead to problematic drug use and limit an individual's options in life.” A truly transformative response would address the underlying political economy of predatory capitalism.

The 270 overdose deaths in Northeast Tennessee last year were not isolated tragedies but the predictable result of a system that transforms pain—both physical and social—into profit, while externalizing the costs to those least able to bear them.

As naloxone becomes more widely available, McCaffrey issues a simple directive, as Keeling reports: "Anyone who loves someone with a substance use disorder needs to have it available and know how to use it." It's a necessary response to the immediate crisis, but the longer-term solution must address the structural conditions that make Appalachia susceptible to predatory accumulation.

Until then, communities like those in Northeast Tennessee will continue to count their dead, while the architects of this crisis count their profits.