"They Can Control the Weather": How Partisan Political Identity and Corporate Interests Profitably Meet in Appalachia

Fossil fuel executives who have altered our climate remain conveniently invisible, protected by weather control narratives that claim to expose hidden power

Hurricane Helene brought two feet of muddy water flooding around Dad's house in Konnarock, Virginia, where I grew up. It was water where water had never been, and it shocked everyone, destroyed much, and raised lots of questions.

Six months after the storm, Dad saw a neighbor in a local grocery store for the first time since the disaster. They talked. Eventually, the topic became the severity of the weather, especially Helene. The neighbor said to Dad: "They can control the weather," which explains the extremes, including Helene.

Dad told him that he'd never heard of such a thing. The conversation ended shortly thereafter.

What does claiming ‘They can control the weather’ mean in America today?

This exchange reveals how weather control conspiracy theories serve a dual function: they mark political identity boundaries while redirecting blame away from the fossil fuel companies actually altering the climate.

Yes, it would be easy to dismiss this guy as crazy. But I’d caution against that hasty move. This kind of weather talk engages in a localized politics that, to expand on Berland, functions as everyday testing for recognition to a particular national-regional identity and loyalty complex.

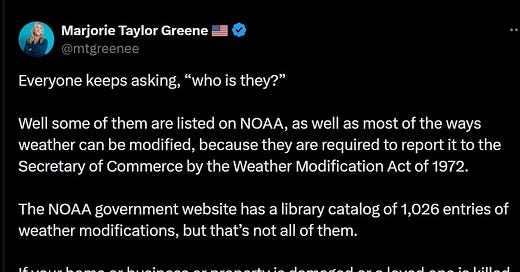

I searched the internet for the phrase: "They can control the weather." I learned that a few weeks after Hurricane Helene, Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia had tweeted "Yes they can control the weather." And then a few days later she posted the above Tweet.

There's a brutal irony in Representative Green’s words and Dad's neighbor's statement. "They" do control the weather—if by "they" we mean the fossil fuel companies whose decades of carbon emissions have fundamentally altered Earth's climate. BP, Exxon, Chevron, Shell, Saudi Aramco: these corporations, and the handfuls of executive decision makers and board members, have exercised a kind of weather control more profound than any conspiracy theorist imagines. But in the Food City parking lot in Chilhowie, this real manipulation was obscured by fantasies of government storm-steering.

This misplacement—from fossil fuel companies to government manipulators—serves multiple functions, providing "someone to blame" while directing blame in a way that avoids recognizing the measurable causes of extreme weather.

Weather talk has served as political discourse in the context of Anglo history for centuries.

Since all daily experienced the weather this could give rise to an everyday politics, participation in which required neither literacy nor print (although the causes and meaning of, especially extreme, weather events were a popular topic in both cheap and learned print). Since talking about the weather was an everyday activity, it was a political resource open to all and anyone could offer an opinion about the causes and meaning of unseasonal or extraordinary weather events. State and church might hope to police print, but controlling everyday talk was more difficult, the more so since in England’s regionally variable climate knowledge of extreme weather events and their meaning might for some be experienced through rumour and report.

A drought or flood might be read as God's judgment on the Crown.

In a similar way, today's weather conspiracies test partisan allegiance. But unlike historical weather discourse that could challenge monarchical or religious power directly, these modern weather narratives infused with partisan political identity protect corporate power by obscuring its central role in climate change. These weather narratives define the parameters of political identity and reinforce political parties, factions, and leaders like MTG who oppose policies that would advance positive climate change action into law.

Greene's tweet performs the partisan political identity for local voices, like Dad’s neighbor, who then re-circulate the narrative. By promoting weather control theories, she offers Republicans a way to acknowledge extreme weather without accepting climate science—thus maintaining party cohesion while protecting fossil fuel interests. Research on Congressional press releases reveals that politicians "remain hesitant to link extreme weather events to climate change," especially Republicans. Greene inverts this hesitancy, promoting a false link that channels real anxieties into politically useful directions. Her tweet didn't create fear in flood-devastated communities; it provided a framework for interpreting the cause of that fear – the Democrats and Big Government are controlling the weather!

Contemporary research confirms this dynamic's consequences. When politicians accurately link extreme weather to climate change, Republican voters view them as "less capable of addressing weather-related disasters" and become "less supportive of efforts to protect against similar disasters in the future". The weather control narrative, however false, paradoxically generates less political resistance among Republicans than accurate climate science.

This research reveals the weather narrative’s political utility: it allows Republicans to process harsh climate experiences without abandoning partisan identity or supporting climate action that might threaten fossil fuel companies.

This traps Appalachian communities in a cruel paradox. The region faces severe climate impacts—temperatures rising "between 2 and 8°F by the end of the century," with "intense precipitation events" becoming more frequent. Yet the political discourse that might address these challenges triggers partisan resistance. The conspiracy theory offers more palatable villains than the truth: it's easier to imagine evil government scientists than to confront systemic fossil fuel dependency.

Real weather modification technology exists but operates at microscopic scales compared to natural systems. Commercial cloud seeding uses "tens of grams" of silver iodide "over hundreds of thousands of acres" to marginally increase precipitation. As NOAA states definitively: "No technology exists that can create, destroy, modify, strengthen or steer hurricanes in any way, shape or form.”

Weather talk as a political battleground reflects the struggles of sense making in everyday life. Dad's neighbor wasn't just sharing a theory—he was testing political boundaries, seeking confirmation of shared identity through shared explanation, probing where Dad’s loyalties lay. This is everyday politics in action.

This isn’t just in Appalachia. In Brazil, facing similar challenges, rural populations turned extreme weather into a "political matter" where "climate is an aspect of spiritual order in the cosmos" that lead to physical attacks on weather forecasters who incorrectly predicted the weather. Like those communities, Dad's neighbor is constructing narratives that explain unprecedented conditions—but their explanations misdirect blame from systemic causes to shadowy cabals.

The weather control conspiracy reveals how political identity and corporate power intersect in climate discourse. By transforming weather talk into partisan political identity, these narratives help fracture communities in ways that leave them more vulnerable to extreme weather and corporate exploitation.